SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Once again, the New Bilibid Prison (NBP) tops the country’s news headlines. A surprise inspection by Justice Secretary Leila de Lima of the Maximum Security Compound of the NBP on December 14 yielded hotel-type amenities found in inmates’ cells.

Indeed, for outsiders, the presence of wide-screen TVs, Jacuzzis, musical instruments, Internet wi-fi, aircon units, imported alcoholic beverages, drugs, and even sex dolls, are unfathomable— it is inconsistent with prisons as places of punishment.

Coupled with previous media exposés, like inmates being shabbily escorted for medical checkups in private hospitals and where they engage in extra-medical activities, like meeting a starlet afterwards – the common and immediate conclusion is that NBP officials are powerless against big-time VIP inmates and too corrupt to control them.

The immediate policy implication is that “heads must roll” and change of NBP leadership is a necessity. Implicit in this policy is the assumption of command responsibility – that there is no way the BuCor Director, or the NBP Superintendent, or other top managers, are not knowledgeable or not complicit to these illicit activities.

To assess the effectiveness of the “heads must roll policy,” one must revisit previous media exposés and see the outcome.

Previous cases

For example, in March 2011, when inmate Antonio Leviste left the NBP for medical check-up in Makati without a medical permit, a media chorus described the incident as “VIP treatment” and called for the removal from office of then BuCor Director Ernesto Diokno.

After an erroneous reply that “they can’t monitor all prisoners at the NBP,” a tacit admission of inefficiency, Diokno was immediately axed. A prison leadership change ushered then BuCor Director Gaudencio Pangilinan to the post, who was likewise booted from office amid accusations of corruption. These leadership changes after a media exposé of the irregularities inside the NBP had become all too common and too predictable without any sustainable impact on the practices and activities inside the prison compound.

In fact, it is too tempting to predict that after the recent media interest on this issue dies down, things will be back to normal – the 19 suspected drug-dealing inmates who were transferred for isolation to the National Bureau of Investigation will soon find a way to return back to the NBP; they will soon reconstruct their kubols, and soon will re-assume a privileged lifestyle.

And even if the current NBP leadership will be revamped, the systemic nature of the problem suggests that a new set of NBP leadership will still face the same enduring problems.

This is not to say that NBP prison managers must not be held accountable for the corrupt practices of prison officers that are under their command. Indeed, some NBP officers actively generate income from these corrupt practices.

However, an individualized approach to this systemic problem will simply make the condition worse. Transfer of a corrupt prison officer to a distant penal colony will simply create a vacuum that will be immediately occupied by another corrupt prison officer who is next in line.

What is therefore needed is a systematic and deeper analysis of the problem in order to develop sustainable and holistic solutions.

Corrupt culture

To provide a holistic understanding of the NBP, this essay utilizes a sociological perspective that highlights the structural, organizational, and cultural characteristics of a penal institution.

The structural characteristics refer to the basic conditions of the prison – the living arrangements of the inmates and the working environment of the prison officers.

Organizational characteristics refer to the coping mechanisms of the inmates and prison officers regarding the deficiencies of the structural conditions – the formal and informal rules and regulations that inmates and prison officers developed in order for the prison to continue its operations.

Cultural characteristics refer to the cognitive narratives that inmates and prison officers utilize to justify their coping mechanisms. These cognitive scripts are learned by inmates and prison officers in a process called prisonization and the cognitive scripts are passed on from generation to generation creating a continuity despite changes in the inmate and prison officer populations.

While not all inmates and prison officers adhere to these, and indeed many inmates and prison officers remain honest, the dominant culture is predatory and corrupt and susceptible to the creation of activities that are bizarre and unfathomable to an outsider.

Take the following example:

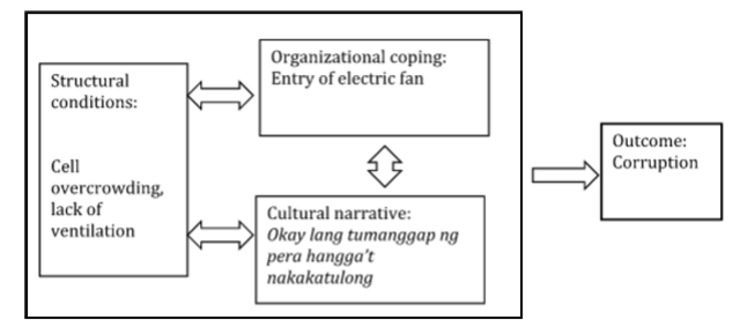

Given the problem of cell crowding and lack of ventilation (a manifestation of a structural condition), a prison officer may justify the entry of an electric fan to a sickly inmate (a manifestation of an organizational coping) and use such narrative as: “It is okay to break a rule as long as it is for humanitarian considerations” (a manifestation of a cultural narrative). As this prison officer continually engages in this behavior, he gains prestige and status in the prison community, in a process called prisonization. Inmates learn of his status and continually seek his favor.

In the short run, this setup provides a mechanism for inmates to normalize their conditions, that is, inmates can have access to ventilation, which is a basic human right in the first place.

In the long run, however, this practice can mutate into corrupt practices, as other prison officers can utilize these dynamics as a pretext to generate extra-income: “It is okay to break a rule as long as it is for hu-money-tarian purposes.”

Hidden problem

While the obvious problem that can be seen is “corruption” and abuse of authority by prison guards, the initial structural problem (that is, cell crowding and lack of ventilation) is usually hidden and not reported.

Efforts to discipline the erring guards through transfer in a faraway penal colony may work in the short-run, but other prison officers will simply fill in the void caused by the transfer, and the practice is again resumed (See Figure 1 below).

Least prioritized

Structurally, the prison system is the least prioritized of all the agencies of the government.

The NBP’s Maximum Security Compound accommodates 14,200 inmates while its ideal capacity is only 4,000, making it one of the most crowded mega-prison in the world.

It also lacks qualified personnel, resources and facilities. The current personnel-to-inmate ratio is 1:80 despite the ideal of 1:7. Thus, as one prison guard remarked, “even if you are a superman, you cannot effectively guard all these inmates.”

Organizationally, inmates and prison guard develop structures to overcome these deficits. Because of the lack of personnel, a system of “mayores” “coordinator” and “trustee” evolved where selected inmates are assigned custodial, rehabilitation and administrative functions, respectively.

Due to lack of facilities, inmates are allowed to construct kubol (cubicles) and tarima (beds) to maximize unused spaces without additional expenses from the government. Inmates are also allowed to construct basketball courts, religious temples, and educational centers in order to augment the rehabilitation programs.

To supplement the limited budget from the government, inmate cell leaders are allowed to collect money from their fellow inmates in exchange for cell privileges like being exempt in cleaning the buyon or rest room. These inmates are called Very Important Preso (VIP), which is a far cry from the “VIP treatment” that the media attached to them.

The cell funds are used for the purchase of inmate medicines, for the upkeep of the cell, and to support rehabilitation programs. All these coping mechanisms that gradually emerged are informal and publicly hidden. In fact, these are strongly prohibited by the prison manual.

As such, prison officers and inmates who engage in these practices know fully well that they can be “exposed” and “be held accountable.”

Yet due to the structural limitations of the bureau, inmates and prison guards are forced to adopt these practices, or else, the bureau will collapse. They are then admonished to be adept in “playing the rules” and know when is the best time to utilize the formal and informal rules.

While these coping mechanisms have short-term benefits, they can have a negative enduring effect to the administration of justice. It creates a predatory culture that tends to perpetuate the structural and organizational characteristics of the prison.

Fighting over spoils

For example, with the emergence of the mayores comes power play among the inmates. Inmate leaders fight over the spoils generated by the prison cash economy. Pangkat (brotherhoods) which started as inmate groups to protect themselves from predatory guards and other inmates, have degenerated as gangs that now give protection to inmate drug dealers.

Awash in drug wealth generated by continuing operations in the outside, inmate drug dealers, with the assistance of the gang bosyos (top leaders), systematically bribe prison guards to engage in unbridled operations inside.

Prison officers, supported by a system of cliques and kamaganak (family ties) in the bureau, engage in predatory practices called “orbit” where they extort money from the inmates in exchange for protection. A patron-client culture develops where inmates and prison guards continually find individuals or groups whom they could trade favors with in exchange of protection and support.

Idealistic and reform oriented bureau directors face a gargantuan task of reforming a Bureau that had been effectively partitioned by different and competing family groups of prison officers. These unseen family groupings and alliances of prison guards frustrate any reforms that are introduced in the bureau.

And as long as inmates develop a support base with enterprising prison officers, they can engage in pre-imprisonment luxuries – the entry of wide-screen TVs, Jacuzzis, music instruments, Internet wi-fis, Aircon units, imported alcoholic beverages, drugs and even sex dolls.

These privileges, however, are tenuous and can be disrupted from time to time, like when the media gets hold of these bizarre practices and place continuous pressure until such a time that the justice secretary herself makes a surprise inspection of the prison.

The outside world will see these displays of luxuries frustrating and unfathomable – yet for veteran prison observers, these are open secrets known by everyone else. The media exaggerate these situations as the trend, as if all inmates have access to these privileges, which is very far from the truth—most inmates languish in decrepit spaces and pathetic conditions, and without the support of their inmate leaders, could have easily succumbed to diseases.

Inmates and prison officers affected by these calls for “heads to roll” understand that this is part of the collateral damage that they simply have to endure. It is a part of the cost of doing business.

They will simply go through the motions, that is, accept the transfer order (in case of inmates) or the “floating position order” (in case of the prison officers) and wait for the issue to to die down. Eventually, when the media attention is centered elsewhere, these inmates and prison officers will slowly crawl back to their positions.

Holistic solution

In short, instead of the myopic and individual-centered approach of dealing with the systemic problem, a holistic and long-term solution must be in place.

The Modernization Law of 2013 and its newly passed Implementing Rules and Regulations is a step in the right direction. Increasing the number of prison officers and improving their quality through proper recruitment, selection and training will be a key in professionalizing the corrupt prison staff.

More regional prisons with a population of not more than 2,000 inmates and with sufficient facilities must be constructed. The plan of transferring the entire 22,000 population of the NBP, which includes the Medium and Minimum Security, prisons, to Laur, Nueva Ecija, must be reconsidered.

A prison with a population of 14,200 is susceptible to the creation of a predatory prison management. An integrated prison system that incorporates the principles of effective correctional management like inmate classification, housing security, inmate programming, and documentation and assessment must be put in place. – Rappler.com

Raymund E. Narag attained his PhD degree from the Michigan State University School of Criminal Justice. He is assistant professor at the Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice of the Southern Illinois University Carbondale. Dr. Narag’s research interest delves on understanding community-based processes that mitigate the proliferation of crime and delinquency.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.